Sorry I'm late! I was swooning over an olive tree

Van Gogh, Lonnie Holley and Abigail's Party are some of London's cultural highlights this week

Sometimes, an exhibition is staged that justifies the overused phrase “must-see”. Sensation, the show that launched the YBAs, at the Royal Academy in 1997, was one of these (I didn’t see it, having not the slightest idea it was happening on my arrival in London as a green and careless undergraduate). Leonardo Da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan at the National Gallery, in 2011, was another (that one I saw twice).

Both of these had their controversies - Sensation was criticised as a bald attempt by organiser Charles Saatchi to raise the value of the work in his collection by placing it in museums. The inclusion and full attribution in the Leonardo show of the famous Salvator Mundi (c. 1499-1510), bought in 2017 at Christie’s in New York for $450.3m by Prince Badr bin Abdullah Al Saud, but how much of which Leo himself actually painted, if any, has long been disputed, kicked off an international scandal of sorts that has rumbled on ever since.

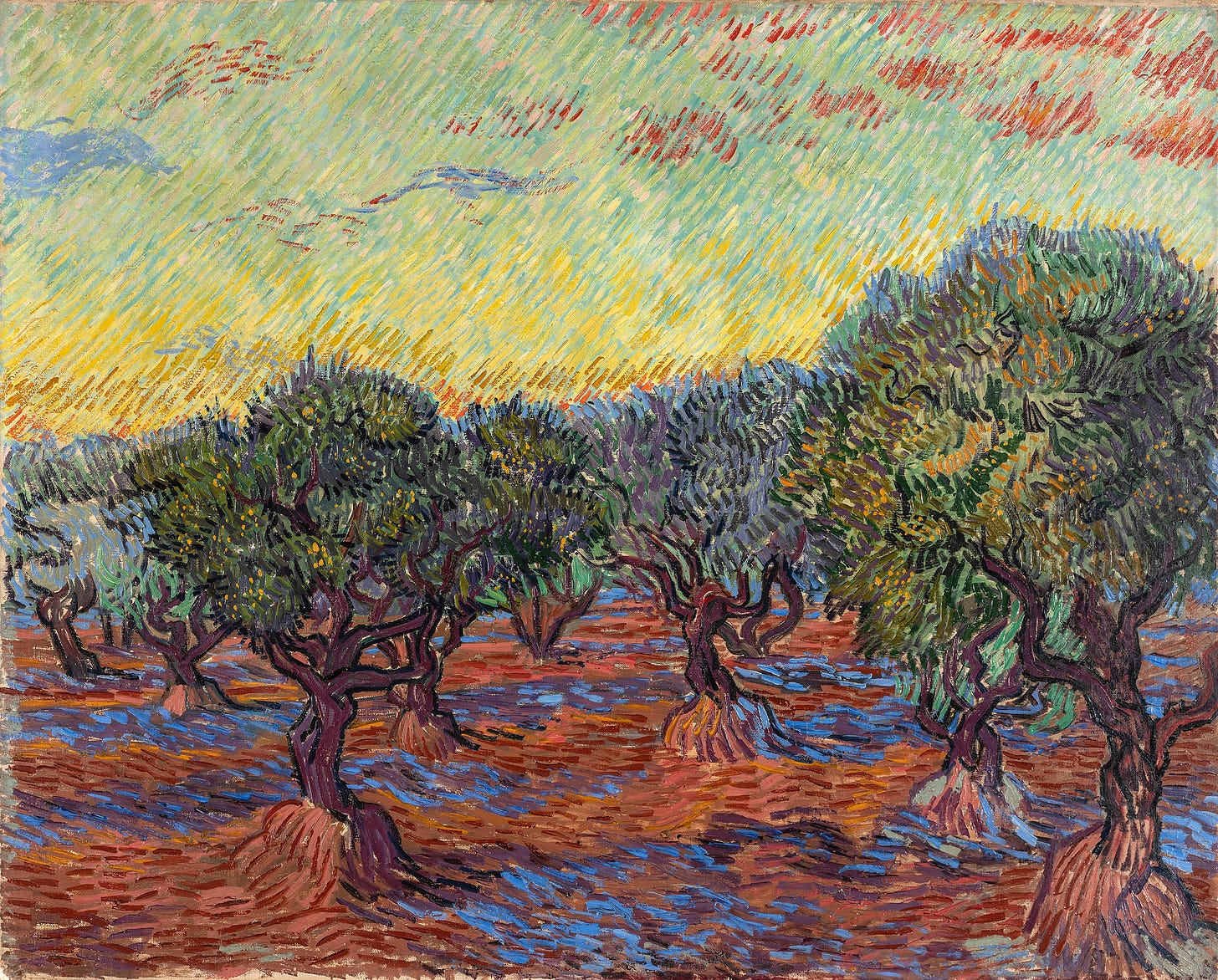

It remains to be seen whether anything especially controversial will come out of the National’s new exhibition, Van Gogh: Poets & Lovers, but my God, see it if you can. It’s wonderful.

Despite his fame and popularity, Van Gogh is one of those artists it’s easy to think you don’t care for. I think that’s at least partly because you genuinely have to see his work IRL to appreciate it. I wasn’t especially bothered until, about a decade ago, I visited Arles and Saint-Rémy-de-Provence (where he was based during the period that this exhibition covers) and I experienced the incredible, near-hysterical light in that region and realised, with wonder, that with his thick impasto lines of mad, swirling colour, that’s exactly what he was capturing, with unreasonable success.

He cares about paint, and you just can’t get the life of what he’s doing in print or on a screen. In Undergrowth, 1899, you can almost feel the cool dampness of the neglected garden at the hospital at Saint-Rémy, and feel the way the sound deadens as you walk beneath the trees. The Sower, 1888, a late afternoon scene of a figure sowing seed beneath a huge, low sun, seems to suck light in hungrily, the way night sucks away the day.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The London Culture Edit to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.