I got back last week from my holiday visiting friends in New York City and upstate in Hudson, which was a joy. In Hudson I did almost nothing except read books (this one in particular was incredible, and I also enjoyed this though I read it for work reasons and it definitely is way more decorous than the whole story, which involved quite a few affairs), walk trails in the Catskills and eat (Klocke Estate, an extremely fancy distillery which opened last July, is a particularly lovely dining experience, with views across the Hudson Valley).

But doing nothing in New York City isn’t quite so easy, so this is a quick, free, roundup of stuff I did. We’ll get back to the usual London bulletin later this week.

The main thing I was excited about before I arrived was visiting the newly refurbished Frick Collection. If you know the Wallace Collection in London, it’s sort of that but on an American scale (Henry J Frick saw it, in fact, and was inspired). Set in the 19th century industrialist’s gorgeous home on Madison Avenue, because of course that’s where it was, it’s an absolutely fantastic collection, mostly of paintings, but also of ceramics, objets (clocks, watches, chandeliers etc) and very fancy furniture, including two pieces that used to sit in Marie Antoinette’s bedroom.

But the house, despite its size, was feeling cramped and not fit for the 21st century crowds of enthusiastic visitors who were making their way there every year to look at the works by Velazquez, Whistler, Holbein (Thomases More and Cromwell glower at each other across a fireplace), Bellini, Fragonard, Gainsborough, Goya and most of the other usual suspects.

The second floor (what we would call the first floor in the UK), once the Frick family’s private spaces, were being used as offices, so ascending the grand staircase for a poke around upstairs remained tantalisingly out of bounds, and some of the collection’s real treats were a bit lost in the bigger public spaces downstairs. Also they needed a decent shop and restaurant, because that’s now the rules.

So they brought in architect Annabelle Selldorf (whose adaptation of the Sainsbury Wing is about to reopen at the National Gallery) and she has done an amazing and highly sensitive job, rebuilding the façade of the Frick Art Research Library and extending it over 20 feet, adding a two-story overbuild in the centre of the building adjacent to the Garden Court for special exhibition galleries, offices and a conservation studio, expanding the reception hall with a stunning additional marble staircase that must have cost considerably more than my flat, and popping on a second storey connecting to the historic house, as well as burrowing out a 218 seat auditorium below the 70th Street Garden.

The rehung and refurbished galleries, though, are a triumph too. With specially commissioned fabric wall coverings and carefully researched efforts to return works to the spots where Frick originally enjoyed them, curators have elevated what was already a stunning place to see art.

The Whistlers, of which the Frick has a very significant collection, positively sing from their new dove grey walls, and Frick’s collection by artists from the Barbizon School has been brought together and given its own dedicated room, emphasising the richness of these landscapes by the likes of Corot, Millet, Daubigny and so on.

Architectural and decorative features have been carefully restored, and new installations put in place inspired by the personal collecting interests of the Frick family: portraits - Henry Clay Frick’s favourite genre - in what was his bedroom; Renaissance gold-ground panels in his daughter Helen’s room; and Impressionist paintings. There’s also the insanely frou-frou Boucher Room, which has been moved from its previous location downstairs to its original setting upstairs, in the former private sitting room of Frick’s wife, Adelaide Childs.

It really is absolutely breathtaking. They’ve also commissioned a lovely collection of porcelain plants and flowers by sculptor Vladimir Kanevsky, paying homage to the floral arrangements made for the Frick’s original opening in 1935, which seems mad but it makes such a difference, shifting the whole vibe of the place from ‘museum’ somewhere in the direction of ‘home’ (though they are so fragile it is absolutely terrifying to get anywhere near them).

The museum’s first special exhibition, Vermeer’s Love Letters, which brings together the Frick’s one example of the painter’s work, Mistress and Maid, with two important loans: The Love Letter from the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, and Woman Writing a Letter, with Her Maid from the National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin, will open on June 8, running to September 8 - but it’s worth a visit any time, genuinely a gorgeous experience.

Having never been to the Met Opera at the Lincoln Center I leapt at the chance to dress up (not required but encouraged) and see The Magic Flute, directed by Simon McBurney. I’ve also never seen TMF, though I knew that it was one of Mozart’s sillier operas.

Reader, it is batshit. Insane. Like a small child telling a story where one incident bears no relation to the next and the basic premise is as substantial as the mist on the Danube. Narratively speaking it’s really not worth explaining, and in any case it’s teeth-grittingly sexist if you actually pay attention so best to let it wash over you.

But the staging is fantastic. McBurney is the man behind the theatre company Complicité, which is responsible for things like A Disappearing Number and The Encounter, and also Mnemonic, which I didn’t much like (though again, the staging was fab) but lots of people adored. Nothing in this Magic Flute is overdone but there is such an ingenious plethora of tricks and novelties that you’re constantly being delighted, and there’s little time to be irritated by the story.

Here a charismatic foley artist supplements the lively Metropolitan Opera Orchestra on one side of the stage, while an artist does live chalk drawings on a board at the other side, projected in real time as a backdrop, serving as mountains, sunrise, announcements of new acts and indicating new characters with big arrows, all kinds of things.

When Prince Tamino (again, it doesn’t matter a jot who these people are, narrative is simply a vague concept here), is meant to be playing his magic flute (I forget what it’s meant to achieve - delight the enemy into submission I think), he simply hands it politely to the first flautist and stands back appreciatively as she plays it.

At one point a camera honed in on a young woman in the audience as a potential date for the clownish comic turn Papageno, the bird-catcher, because that’s a job (the birds are members of the chorus fluttering A4 sheets of paper folded down the middle). She fully understood the assignment - her little heart hands 🫶 got one of the biggest roars of the night.

Of course the singing was lovely. Golda Schultz as Pamina was particularly heart-piercing, and Kathryn Lewek made an excellent fist of the coloratura (lots of vocal acrobatics) Queen of the Night, while being rolled around in a wheelchair quite a lot of the time. Clearly it was meant to indicate her weakness as her power diminishes but it served mainly to remind me that it is vanishingly rare to see an actual visibly disabled person on an opera stage, at least in my experience. It feels like there can’t be a good reason for that except that they’re not encouraged to perform when young, so that seems like something that needs addressing.

The famous QoN aria is this one - I hadn’t actually realised it’s a song in which she’s demanding that her daughter murder someone. Ben Bliss as Tamino had a lovely warm sound and was amiably exasperated, and Thomas Oliemans as Papageno was actually funny.

It was really fun. Totally daft. At three hours I’m not sure I’d recommend it for kids, per se, but duration is really the only reason. It’s a good opera for people who think they don’t like opera. It’s just ended, but I can’t imagine it won’t come back at some point. The point really is that the experience at the Met is great, even if you don’t know what you’re in for.

The fact remains though that unless you sit up somewhere in the gods, it’s not cheap (if you do, it actually is far more affordable than Broadway. You’ll notice I didn’t set foot on Broadway the whole trip, for this reason). Fortunately there are other options if you happen to love or be intrigued by opera.

I didn’t realise, having never thought about it, that the talented instrumental and vocal students of the Manhattan School of Music stage full-scale operas - along with smaller, chamber operas, and also of course loads of classical and jazz recitals - in an impressive auditorium, for a top ticket price of $30. Quite a lot of their concerts are free.

I saw the final performance in their run of the opera Rusalka, by Dvorak, which I didn’t know at all and is based on a folk tale, variations of which bubble up across numerous cultures, and is the basis for The Little Mermaid, except that nothing good comes of any of it.

Rusalka, a water sprite, falls in love with a human prince and yearns to escape her watery world for the land above - but there’s a catch, of course, in this case quite a number of slightly vague, complicated catches, in addition to the one where she can’t actually speak to him once she’s out and breathing air.

The music is gorgeous, it turns out, and the cast I saw (which was the second cast, meaning in this case that apparently they didn’t have quite such big voices but several of them did actually know how to act, this being the hierarchy in the world of opera) performed it with brio and conviction. I thought the singing was great, personally, and I especially liked Donghoon Kang as Rusalka’s father, the water goblin Vodnik, and Xiaowei Fang, thoroughly enjoying herself as the witch Ježibaba, whirling about and cackling in a fabulously austere frock.

The design was… curious. The director, John de los Santos, took inspiration from the fact that the MSM sits on the site of part of the Bloomingdale Insane Asylum, a glorified prison into which individuals - especially women - were thrown on the basis of no meaningful diagnosis and with no agency to get themselves out.

At the time of the opera’s composition, 1900, Bloomingdale was particularly keen on hydrotherapy, a soothing-sounding term for forcibly submerging people in cold water for extended periods among other unpleasant aquatic tortures. So the water sprites are all filthy inmates with matted hair and ragged clothes, and Rusalka (Kemeng Zhang) a foundling who has spent her life at the hospital. The handsome prince (Wonjin Choi, who warmed up nicely actually) is the hospital’s benefactor, Vodnik some kind of harried but kindly doctor and Ježibaba a sadistic surgeon. Or something. The set was a disused swimming pool with beds in it.

I always find it a bit frustrating when opera directors overlay some mad scenario on an already preposterous narrative (a maddening production of Mozart’s La Clemenza di Tito, which is set in Rome and involves the destruction of the Capitol, which I saw that the Royal Opera House transposed to a boy’s school, springs to mind) with apparently no thought to whether it serves the story or not. De los Santos at least did it for a reason, and it just about worked - and the supernatural always makes the madness easier to swallow.

I enjoyed it, and actually, knowing that these are young performers still in the course of their studies makes it rather a lovely experience. You’re rooting for them, so when they nail it, it’s fab. You can find their upcoming performances here.

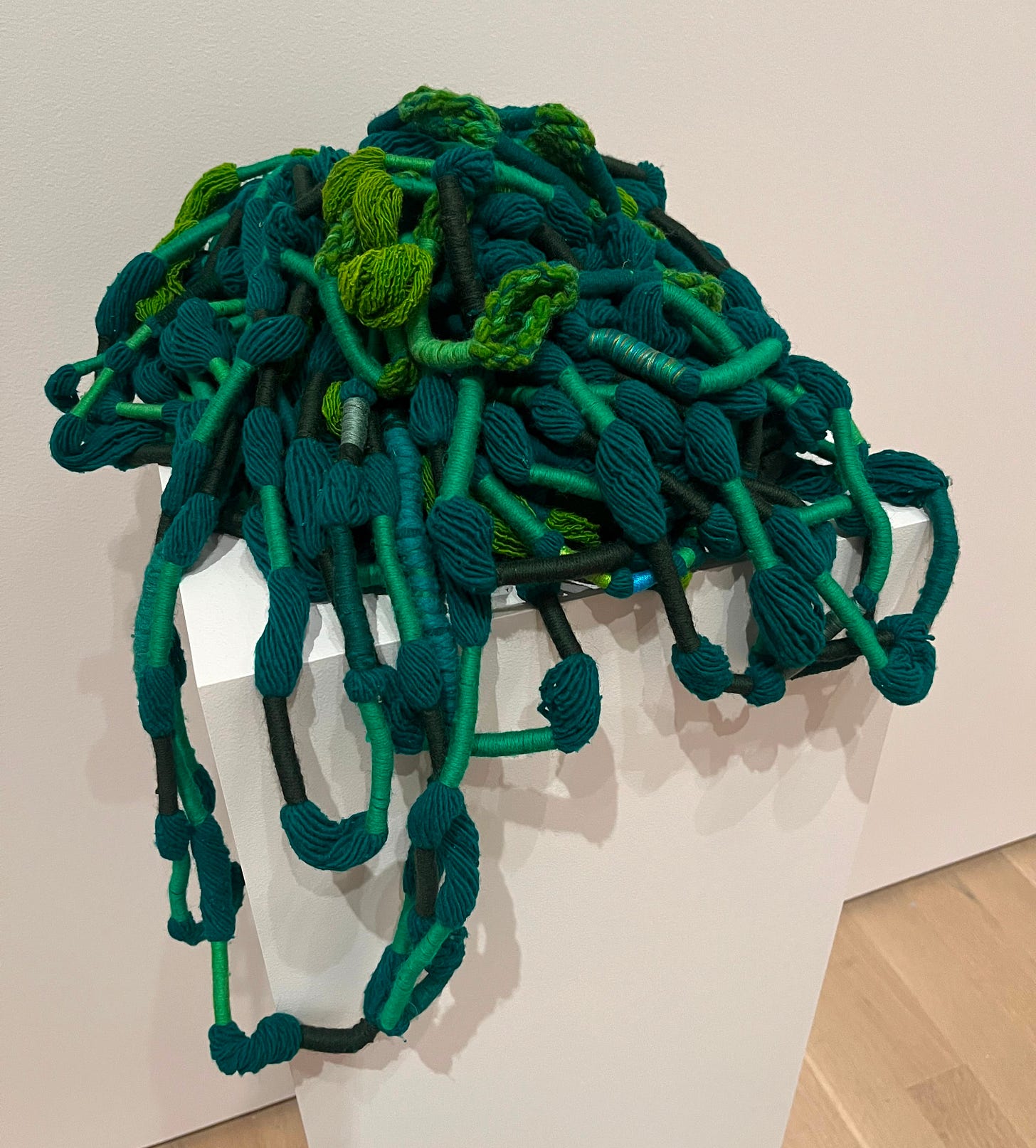

The rest of what I saw was art. I adored Woven Histories: Textiles and Modern Abstraction at the MoMA until September 13, which uses about 150 textile works from the early 20th century to today to explore how modern artists have used weaving (along with a range of other media, but focused on that) in the overlap between abstract art, craft, and fashion.

It’s got lots of the big names you want in a textile show - Sonia Delaunay, Anni Albers, Liubov Popova, Hannah Hoch, Lenore Tawney, Rosemarie Trockel, Ruth Asawa, Sheila Hicks, Eva Hesse - and loads I didn’t know, like Harmony Hammond, whose painted oil and wax pieces are incised with a grid to give them a nubbly woven-like texture, or Yvonne Koolmatrie’s sculptural works made with the coiled-bundle basketry technique of her Ngarrindjeri heritage.

I really liked Carole Frances Lung’s 2015 video work Frau Fiber vs. the Circular Knitting machine, in which her alter-ego sits and knits a tube sock from scratch over four and a half hours, while a high-tech automated machine next to her produces 99 pairs (a cheeky critique of the romantic view of handcrafting as a form of creative expression), and Ann Hamilton’s side by side coats, 2018/2023, for which she needle-felted raw fleeces into thrifted coats to highlight the enduring interdependence between human and animal, and the disconnect/connection between the manufactured and the organic. They’re sort of fascinating and comforting and creepy at the same time.

I think it’s the tactile nature of textile, and its association with the body that makes it so, well, intricately woven into our culture. I’ve written about this before so I won’t repeat myself, but I find it irresistible. This is a really gorgeous show.

Totally different but utterly fascinating was The Book of Esther in the Age of Rembrandt at the Jewish Museum, which runs until March 10. For those among us who are unfamiliar with that bit of the Old Testament, the story (which is traditionally read on the Jewish holiday of Purim) goes that the Persian king, Ahasuerus (AKA Xerxes I) holds a beauty pageant to find a new queen, won by a young woman named Esther. She becomes queen, but keeps her Jewish heritage a secret.

When Esther’s cousin Mordecai refuses to bow to the king’s deeply unpleasant advisor Haman, Haman plots to kill all the Jews in the kingdom. So Esther bravely goes before the king without being summoned (highly risky, against the law, could end very, very badly) and invites him to a banquet, attended also by Haman. All is jolliness and festivity, until Esther reveals herself as Jewish, and tells the king of Haman’s plot. He’s appalled (at his vicious advisor, fortunately for our heroine) and Haman is hanged on the gallows he had built for Mordecai.

The subject - particularly the moment of revelation at the banquet, which has so much opportunity for drama and indeed many of the depictions show evidence being influenced by theatre conventions of the time - was especially popular for paintings in Amsterdam among the merchant class (who were the people buying them), for whom Esther’s heroism came to represent their emerging nation’s identity - the Dutch republic was at this time embroiled in a number of conflicts, including the overlapping Eighty Years War, against the Spanish Empire, and Thirty Years War, which has something to do with the Holy Roman Empire but which I have tried and failed to completely puzzle out so I’m not going to be definitive about who was fighting against whom.

Rembrandt and his contemporaries depicted scenes of Esther’s story in paintings, prints, drawings, and decorative arts, including scrolls (oooh there are some lovely ones here, but you’ll need your glasses, some of the illustrations are teeny wee), and my favourite object here, apart from the astonishing Rembrandts, of which there are a couple, is a lamp, made in a traditional Jewish form but out of the typically Dutch blue and white porcelain.

Amsterdam was one of the most relaxed places for Jews to live in Europe, eventually giving them the right to practice their faith and accepting that they were very useful people to have around, and this object to me gives full expression to the owner’s pride in being both Jewish and Dutch, a contributing member of a new nation. It’s a super interesting show, and in the afternoon it’s almost empty, so quite a lovely relaxing experience, which the Frick, with the best will in the world, right now is not.

That’s all for today, the rest of my time in New York was spent shopping and eating and walking up and down very long streets. Come back on either Thursday or Friday (this week is quite something, so I’m hedging my bets on when I’ll get it done) for the first big London bulletin of the spring.